Owens Thomas House and Slave Quarters: Tale of Two Histories

The Owens Thomas House and Slave Quarters

Historical buildings, such as the Owens Thomas House and Slave Quarters (OTHSQ), are a telltale of a completely different era that bears a stark contrast to the freer modern society.

Or does it?

The extravagance and imperial aesthetic of the mansion may have impressed me at first but it left me in tatters to see the other side of the same regal estate – the Slave Quarters. All the glitter washed away in an instant when I saw the empty rooms with less than bare minimum facilities. It stank of unconditional, unfair, and perpetual servitude.

Please make a point to visit the Owens Thomas House and Slave Quarters. It will take you about an hour or less to walk through the entire tour. However, this is not an experience you should miss if you have the opportunity to grab it.

Now let’s talk about the home, the tour, and its present-day historical and cultural significance.

Living Inside the Gone with the Wind Universe

While the cringeworthy book shamelessly romanticizes “The Great South,” it acts as an ugly reminder of the murky past. A universe of horrible things done by one “class” to the other come undone in these thousand pages. To stand between the mansion and its heart-breaking counterpart is to witness history frozen.

1939 Publicity photo for the film adaptation of Gone with the Wind featuring Hattie McDaniel, Olivia de Havilland and Vivien Leigh: MGM / Public domain

How did the woe of one become the wealth of another?

When Savannah’s cotton industry began thriving, it made the once-impoverished European immigrants, successful plantation owners. An unspoken sense of competition took over the South. Ladies started sporting muslin dresses, Moroccan slippers, and matching frilled hats. And the men demonstrated wealth in the expansiveness of their estate, exclusive interior décor, and the number of enslaved people they owned.

In just 25 years between 1750 and 1775, Antebellum Georgia’s enslaved population increased from less than 500 to over 18,000. By the year 1800, the number of enslaved had doubled, only to reach a massive number of 105,218 by 1810.

It’s illustrated all too well in the book and namesake movie of Margaret Mitchell. Its racist depictions, brutal portrayal of slavery, and display of self-centered plantation owners are grating. But when standing between the two worlds of OTHSQ, it was all so real and in my face.

While the book was set between 1861-1877, it almost entails the “weeping time,” the time when the biggest auction of 460 human beings took place and not far from the Owens Thomas House.

Joseph Bryan (1812–1863), auctioneer / Public domain: This advertisement in The Savannah Republican on February 8, 1859 reads:

FOR SALE. LONG COTTON AND RICE NEGROES.

A Gang of 460 Negroes, accustomed to the culture of Rice and Provisions; among whom are a number of good mechanics, and house servants. Will be sold on the 2d and 3d of March next, at Savannah, by JOSEPH BRYAN. Terms of Sale—One-third cash; remainder by bond, bearing interest from day of sale, payable in two equal annual instalments, to be secured by mortgage on the negroes, and approved personal security, or for approved city acceptance on Savannah or Charleston. Purchasers paying for papers. The Negroes will be sold in families, and can be seen on the premises of JOSEPH BRYAN, In Savannah, three days prior to the day of sale, when catalogues will be furnished. *** The Charleston Courier, (daily and tri-weekly;) Christian Index, Macon, Ga; Albany Patriot, Augusta Constitutionalist, Mobile Register, New Orleans Picayune, Memphis Appeal, Vicksburg Southern, and Richmond Whig, will publish till day of sale and send bills to this office.

A Painful Mélange of Two Worlds

Upon entering the dreamy-looking estate, I felt I was prepared and somewhat aware of what I was going to witness but, its enormity still left me dumbfounded. This place embodied the ambiguity of being Black and Essential, yet given the least to survive on. It reeked of 18th-century racism and I could not shake a personal connection to the home the whole time I was there. I’m shaking as I write this.

On one side, of the garden were those, who despite being the soul and creators of the comforts and care of the likes of Owens Thomas House, were the victims of racial discrimination and brutality. Those who absorbed and carried the rage of their “owners.” They were physically assaulted, sexually abused, restricted from practicing their culture, and forbidden from speaking their native languages. These people were not permitted to educate themselves or go to schools as they could become too powerful or free for the “owners.”

Racism in the South was raucously loud in the two-story, six-chamber quarters designed for those who were responsible for keeping the imperial mansion impeccable. I saw the difference highlighted in the wooden crate beds and cramped rooms. Only a few essentials like brick fireplace compared to the luxuries of the mansion visible from the window of the quarters.

It is the haint blue paint that speaks of their true identity as humans with their own culture and values instead of slaves imported as cargo. The paint was made by mixing indigo, lime, and buttermilk. It was believed to protect the inhabitants from evil spirits.

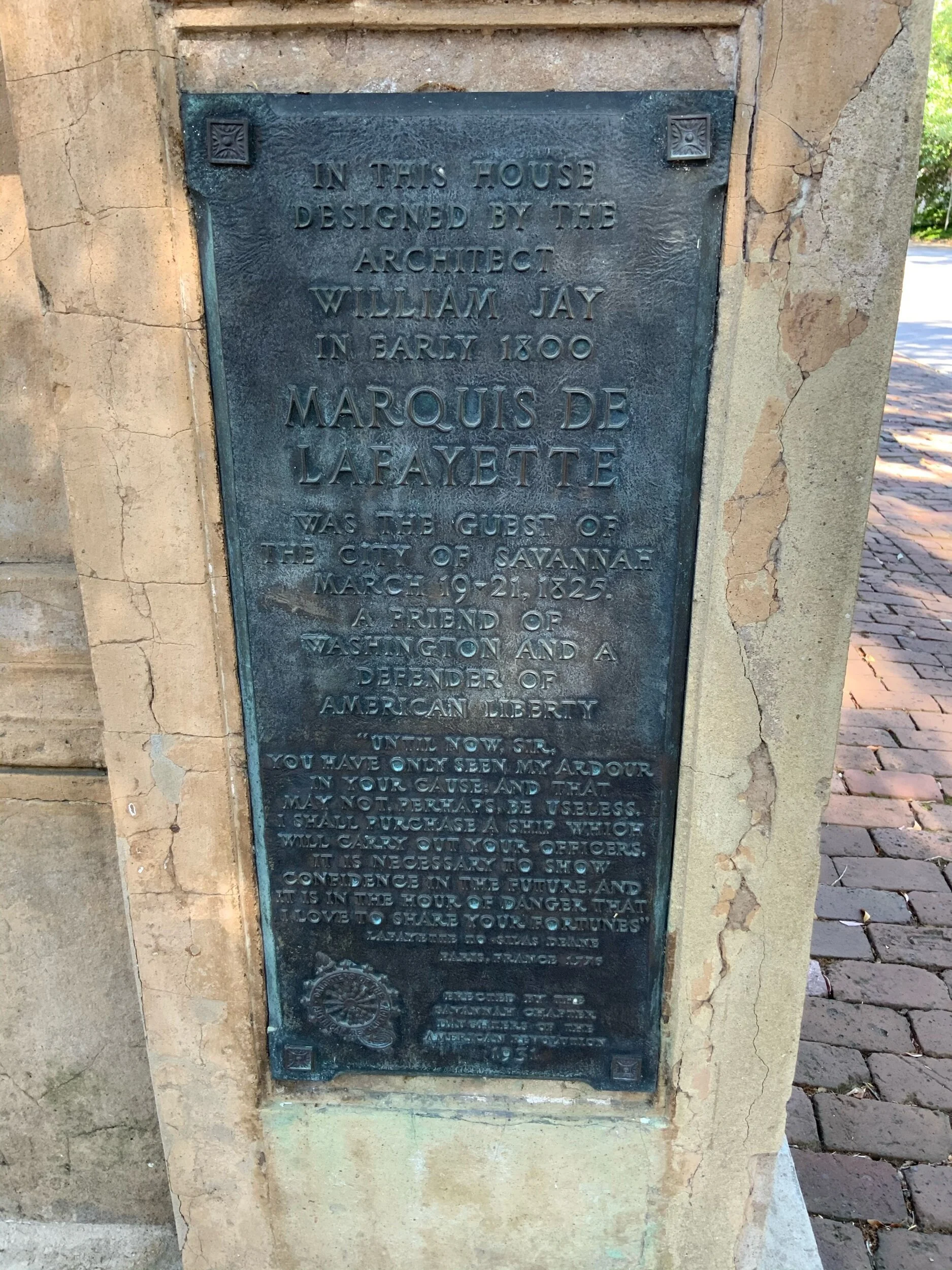

On the other side of the garden, was the awe-inspiring mansion designed by the renowned William Jay in the Regency style, influenced by King George IV, ancient Rome, and Greek architecture. An ultra-opulent space strewn with wooden furniture, a mahogany staircase, cast iron-adorned rooms, marble fireplace, and bronze hardware. Add to the extravagance the luxurious details of intricate plasterwork, carpeted floors, and large windows overlooking a peaceful garden.

The respectable landowner George Welshman Owens who held prominent social posts like a politician (Congressional representative) and a lawyer lived in the large mansion. A well-educated man who was an alumnus of Harrow School and Harvard University, frequented by the high authorities and other nobles of Georgia.

While I still enjoy the beauty of the detailed architecture and furnishings, it pains just a little to look at it. There was something about walking through the Owens Thomas House and understanding the toil that my ancestors undertook to keep up this beautiful home and its furnishings.

There were several points in the tour where my husband stopped to ask me if I were alright. He knows when my wheels are spinning.

I became tearful when we stood in the music room. Here, we learned of the academic rigor of the Thomas children. Earlier in the tour, we had learned that enslaved children learned how to be proficient at their one trade and that was usually what they practiced for life. Things like this make me curious about the long-lasting effects of slavery on African-American culture and our exposure to none-career or job based skills (more on this observation later).

The beauty and charm of the house were crippled when I saw how those who built, worked and cared for it was forced to live.

What I learned during the tour and self-run research was insufferable. Let’s look deeper into the lives of those that lived in the main home.

Lives of the Enslaved Outside the Slave Quarters

The daily routine of the slaves or the workforce of the house had a lot on the plate. They cleaned the house, cooked the food, cared for the horses, drove carriages, bought groceries, and raised the family children. Even the working cellar level, which included the scullery, kitchen, bathing chamber, large cistern, and the cellar, did not get much attention. They were kept simple, underground, and often hidden from the sight of the visitors.

Scullery

The house maintenance rules were stringent. The crown molding was dusted many times a day. The carpet, which was the symbol of wealth in the house, was taken apart, beaten, and washed spot-cleaned in boiled water at least twice a week. The labor who helped with running these tedious errands also included children.

Meanwhile, the owners of the house earned wealth off this institution of slavery. Most of Richardson’s and George Owens’ money came from the domestic slave trade and hundreds of bound laborers on plantations.

The Unknown Story of Emma, Peter, Diane, & Dolly

Perhaps, the biggest problem with the interpretation of slavery is that the decorative art and refine furnishing of the house remain preserved but, the names of those who built and cared for them are still unheard. We know how the mansions look but, without the labor of the enslaved, the house, the wealth, and the prestige of this house wouldn’t exist.

It is rarely shocking because the names of these bound, freedom-deprived humans were too piddling to address in any documents except the receipts.

The men, women, and children who gardened, cooked, cleaned, shopped, and cared for the homeowners remained unacknowledged by the rest of the world.

This anonymity, however, is typical of any privileged white landowner throughout the south. It was also partly because of the 1839 ordinance. The law prohibited anyone, including the whites, from teaching people of color to read or write.

These “invisible people” were somehow brought back to existence when the names of 200 people were known. Note that over 400 persons were working for the Owens. And of them, 8-14 were living in the slave quarters at any given time.

The wall of names of verified enslaved persons who worked in the Owens-Thomas House over the years.

Among all the known names, the four most prominent ones are of Emma, Diane, Dolly, and Peter.

Emma was the maid at Owens’, Peter was the butler, Diane was the skilled cook, and Dolly’s identity is still a mystery.

The lives of the people who lived and worked inside the estate were different from the plantation workers. Those living inside were at the beck-and-call of their owners at all times. Diane, a skilled cook, alone cooked complex meals for up to twenty people alongside the Black butler, Peter. It was not uncommon for them to work from the break of dawn until sundown.

And yet, despite being such a critical part of the household, the likes of Diane were totally dependent on the house owners for the most trivial needs. Everything from how much food to feed their (enslaved) children to what medicine an unwell person (enslaved) can have was dictated by Sarah Owens.

Complicated Slaver to Enslaved Relationships?

Another thing I learned at the OTHSQ is that the relationship between the slave and the owner wasn’t easy to understand. It was no linear lines to connect the dots that easily.

A relatively positive side of the nuance of a slave-owner relationship also existed, even in the Owens House. Emma, who raised multiple generations, including George Owens and his son, was left money in both their wills. She was also taken to Philadelphia for medical treatment once, which was unbelievable.

But it cannot be overlooked how Emma had dedicated her entire life to the family and after she left behind her heritage to embrace theirs. Plus, she was once sent to jail for a night, which is hardly justifiable even if it were for safekeeping.

Where Does the Knowledge of Enslaved Lives Come From? – A Shocking Revelation

Although much knowledge comes from the personal Owens letters and period documents. There is an entire area of the home devoted to historical evidence and documents that tell the story of the past of this home and the relationships between the people who lived and worked in it.